Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum

(Translated from the Chinese version with the help of Claude.)

At the end of June, I visited the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum located at Pier 86 on Manhattan’s west side. After procrastinating for a month and a half, I’m finally writing this travel blog combining my memories, photos, and the guided tour from Bloomberg Connects.

USS Intrepid Aircraft Carrier

Although the museum is named after the Intrepid aircraft carrier, the main exhibits also include the USS Growler submarine, Concorde supersonic jet, and Space Shuttle Enterprise. Below I’ll describe them in the order they arrived at the museum.

USS Intrepid Aircraft Carrier

History

Launched in 1943, it was decommissioned after WWII but was refitted and made a “comeback” in 1954. (Did Jordan learn this from her?) During the Cold War, it was deployed in the Mediterranean, prepared to retaliate if the US was attacked by the Soviet Union. During the Space Race, it served as the primary recovery ship for Mercury 7 in 1962 and Gemini 3 in 1965. It participated in the Vietnam War in 1966. Decommissioned in 1974, it opened as a museum in 1982.

USS Intrepid's main deployment locations throughout different periods

The aircraft carrier is massive, with many levels from bottom to top. Let me walk through them with pictures and commentary.

Third Deck

The lowest level open to visitors, where the crew used to eat and sleep.

Hammocks. This one room must have housed dozens of people. The exhibit even plays snoring sounds. Conditions were quite harsh. With aircraft taking off and landing constantly, you had to adapt to the noise. A small amount of personal belongings could be stored under the mattress. It was hot at night with no air conditioning - the all-steel ship was like an oven. Some people took their mattresses to the flight deck to sleep outdoors.

Recreation room. I think this was for officers? Can't remember...

Hangar Deck

The main exhibition hall.

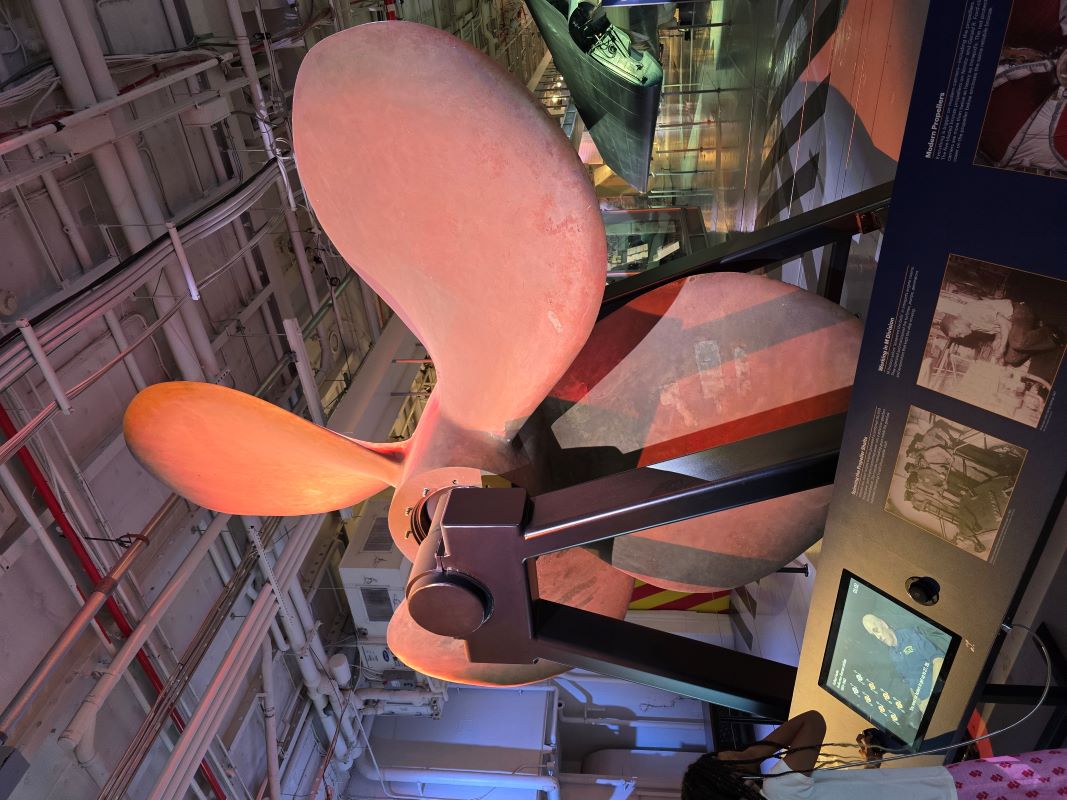

Propeller. The ship had four of these in total.

Steam accumulator. It stored energy using high-temperature steam and released it during aircraft takeoff to help accelerate planes. High-temperature steam was dangerous - from WWII through the Vietnam War, over 150 people were lost in combat, with more than 50 dying from accidents rather than enemy action.

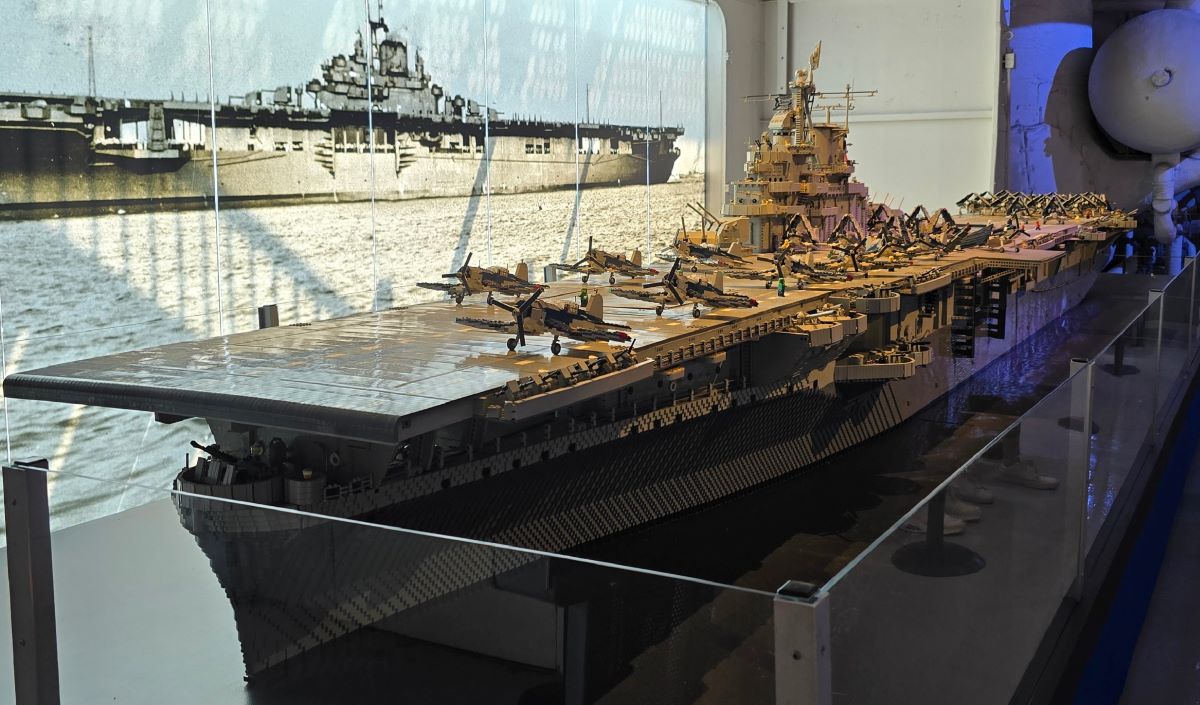

LEGO model. Sponsored by British Airways. The Concorde is also British Airways', so BA seems to have a good relationship with the museum.

LEGO model details

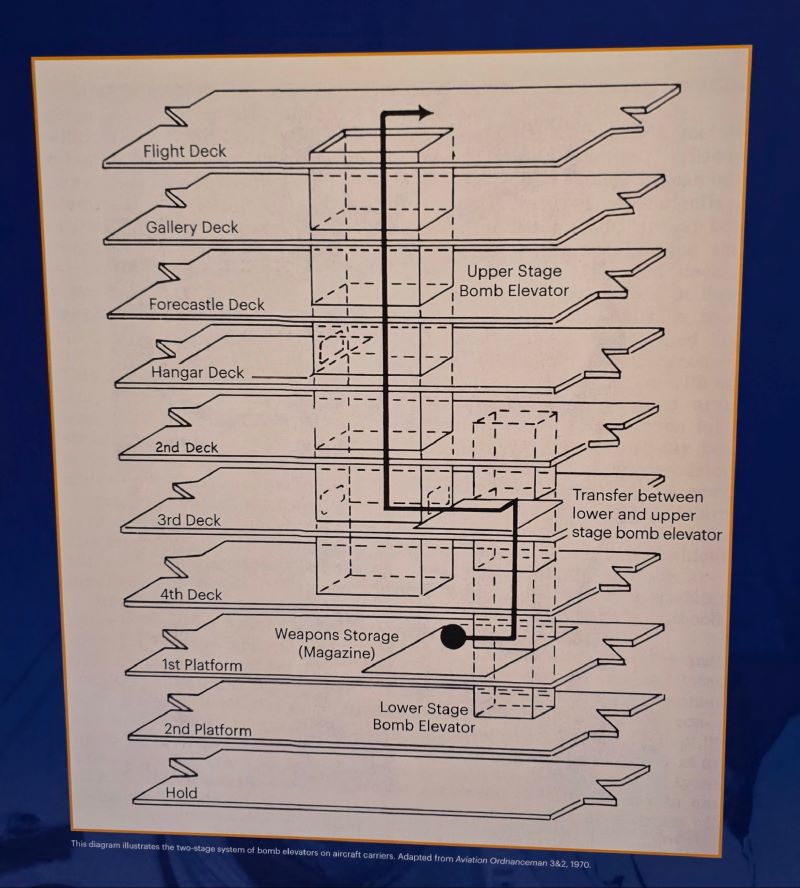

Bomb elevator, transporting ammunition from the magazine to the flight deck. Notice the elevator is divided into two sections and doesn't directly connect the magazine to the flight deck - this prevents accidents during transport and stops ammunition from falling directly into the magazine and causing explosions. The diagram also shows the many levels of the aircraft carrier. People on the flight deck are distinguished by color according to their job - those handling ammunition wear red.

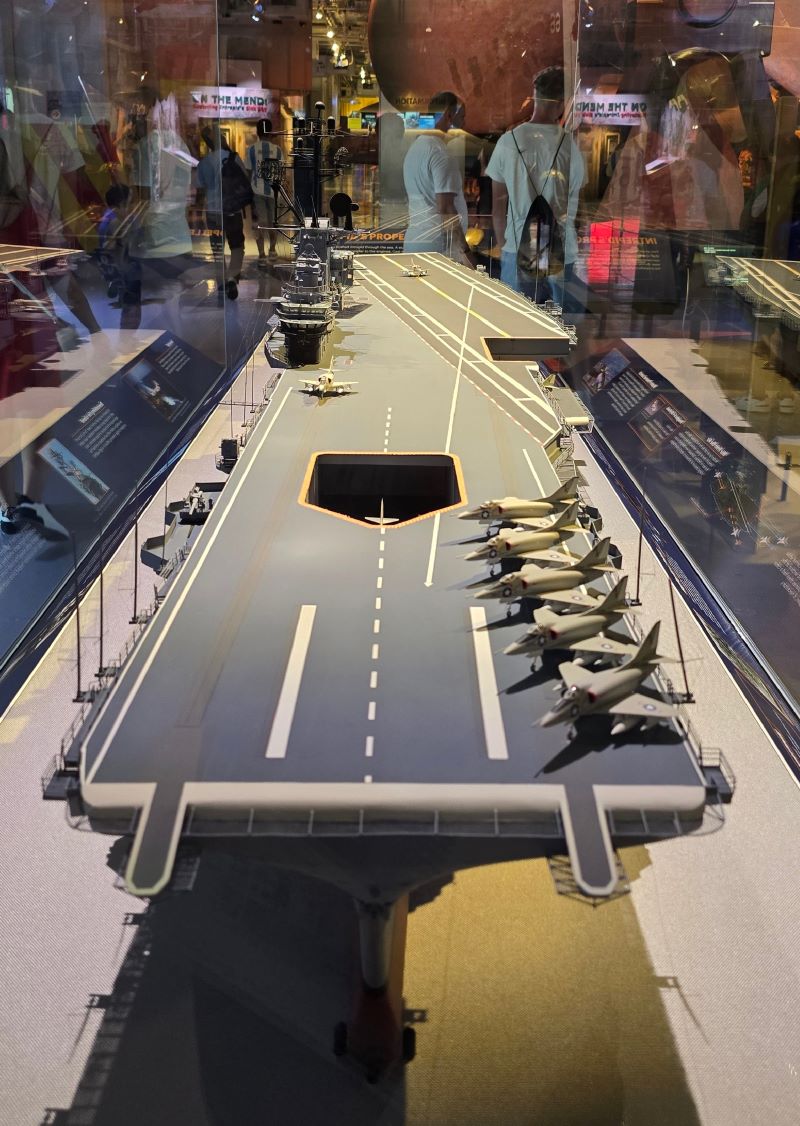

WWII flight deck. Both takeoff and landing used the same straight runway. When other aircraft were taking off, planes couldn't land. If a landing aircraft missed the arresting cables and crash barriers, it would collide with other people/objects on the flight deck - very dangerous.

Vietnam War era flight deck. Landing aircraft used a separate angled runway and could take off again if necessary.

On November 25, 1944, the Intrepid was attacked by two kamikaze aircraft. The fuel-laden planes caught fire one after another, but after several hours of fierce fighting, the fires were extinguished. When they counted casualties afterwards, 69 people had died. The short film below describing the situation plays at the exact spot where the planes struck that day. War is cruel - may there be peace in the world!

Gallery Deck

I didn’t have time to visit that day, but just reading the guide was quite interesting.

Officers’ quarters were located on this level. With 3,000 people on board, about 300 were officers, including not just the commanding officers I imagined, but also pilots, doctors, dentists, chaplains, etc. They had larger living spaces, ate better food (lobster and steak), and had personal stewards to clean their quarters.

Stewards were typically Filipino, Black, or Guamanian, responsible for serving in the dining room, washing clothes, cleaning, etc. Due to racial discrimination/segregation issues, this role has since been eliminated. (What goes unsaid is that this work still needs to be done by someone, regardless of what they’re called, right?) Historically, the Navy was the most “white” branch of the military, and multiple aircraft carriers experienced racial riots. However, stewards could eat in the officers’ mess, which was considered a special privilege.

There were 100-150 pilots (2008 Republican presidential candidate McCain served as a Navy pilot aboard the Intrepid). Their work was more dangerous and stressful than regular sailors, so their special privilege was: the ready room had air conditioning😅

Flight Deck

A-12 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, capable of flying at 80,000 feet - more than twice the altitude of commercial airliners - and at three times the speed of sound, four times faster than commercial aircraft. Its design somewhat resembles the Concorde, though the A-12 had only one pilot while the Concorde carried 100 passengers.

The flight deck also houses the island, which contains the navigation bridge where the captain and officers control the ship’s navigation (for example, when aircraft take off, they adjust course so the bow faces into the wind while sailing at maximum power to help planes take off against the wind), as well as the flag bridge for commanding the entire fleet when the ship serves as a flagship.

USS Growler Submarine

The submarine is located on the north side of Pier 86 and served during the Cold War from 1958 to 1964. Its mission, along with four other submarines of the same type, was to conduct nuclear deterrent patrols near military facilities on the Kamchatka Peninsula (reportedly this naval base abandoned in 1996). If nuclear war broke out between the US and USSR, it would immediately launch nuclear missiles at targets. It carried four Regulus I cruise missiles (Regulus is the brightest star in the constellation Leo, and in Chinese astronomy, it’s the 14th star of the Xuanyuan asterism in the Azure Dragon constellation - though the US Navy wasn’t paying homage to the Chinese ancestor Yellow Emperor😅), with a range of 500 miles. These missiles had to be launched from the surface. It was generally believed that launching the first missile would reveal their position, as the submarine had to maintain communication with the missile throughout its flight to the target. Fortunately, during eight patrols between 1960 and 1964, the Growler never received orders to fire. The later-developed Regulus II nuclear missile had double the range at 1,000 miles, but the program was canceled in 1958 because the next-generation Polaris ballistic missile, which could be launched underwater, was developed, making this submarine obsolete. Many submarines of the same type were later sunk as targets (quite wasteful), but in 1988, the Growler came to the museum.

USS Growler with Regulus missile in launch position

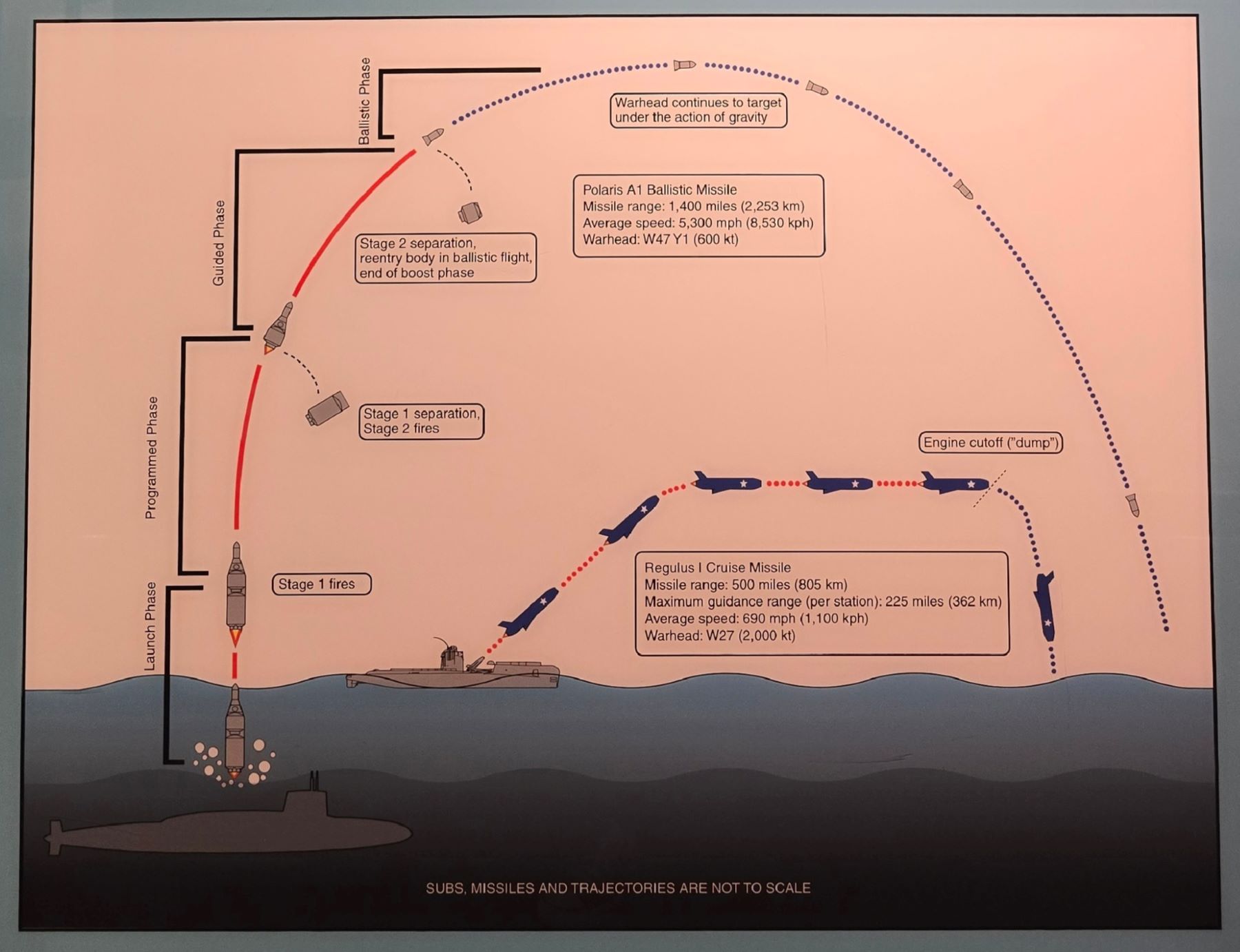

Comparison between cruise missiles and ballistic missiles. In the early Cold War, cruise missile technology was more mature and safe, so the Navy quickly deployed the Regulus cruise missile.

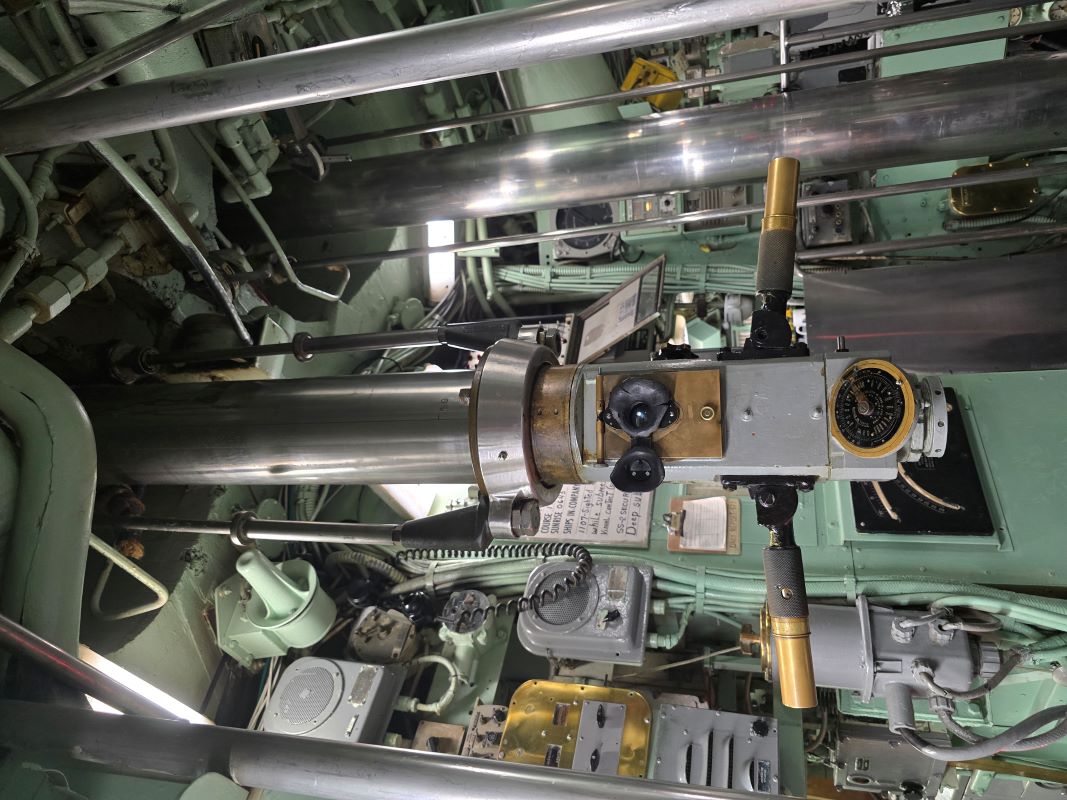

You can't visit a submarine without checking out the periscope

During each patrol lasting 55-79 days, 100 officers and crew were crammed into the narrow submarine with no sunlight, eating the same food and breathing the same stale air. The distance between everyone was smaller compared to on the ships, physically and metaphorically. Everyone on the submarine was a volunteer - no one could be forced to serve on a submarine. With people seeing each other constantly (“looking up and down, you see the same faces”), interpersonal skills were even more important. Everyone had to master all systems (sonar, radio, etc.) so they could replace each other in emergencies. The submarine had no laundry facilities, so clothes were worn repeatedly (this is a bit disgusting… surely they hand-washed underwear?!)

Personal items could be stored under the mattress. Common items included books, magazines, games, cigarettes (smoking wasn't banned on submarines?!).

Concorde Supersonic Jet

Although I didn’t have time to see it that day, the Concorde’s supersonic flight laid the foundation for later Airbus aircraft, and its historical significance is undeniable. The Concorde could carry 100 passengers and reach twice the speed of sound - any faster and the aluminum fuselage couldn’t withstand the heat. To achieve such high speeds => triangular wings were needed => but there wasn’t enough lift during takeoff and landing => the angle of attack had to be increased => pilots couldn’t see the runway ahead => the nose bent downward during takeoff and landing. That’s quite a long causal chain, demonstrated in this video:

The Concorde at the Intrepid served from 1976 to 2003 and arrived at the museum in 2004 (all Concordes were retired in 2003 due to safety issues and the aviation industry downturn after 9/11, and are now displayed in Europe and North America). In 1996, it set a record of under three hours from New York to London. Creating this record required perfect timing: strong tailwinds plus communication with London air traffic control to get permission to land eastward at Heathrow, allowing the plane to fly at high speed longer as it approached Heathrow instead of slowing down to turn around and land westward.

Space Shuttle Enterprise

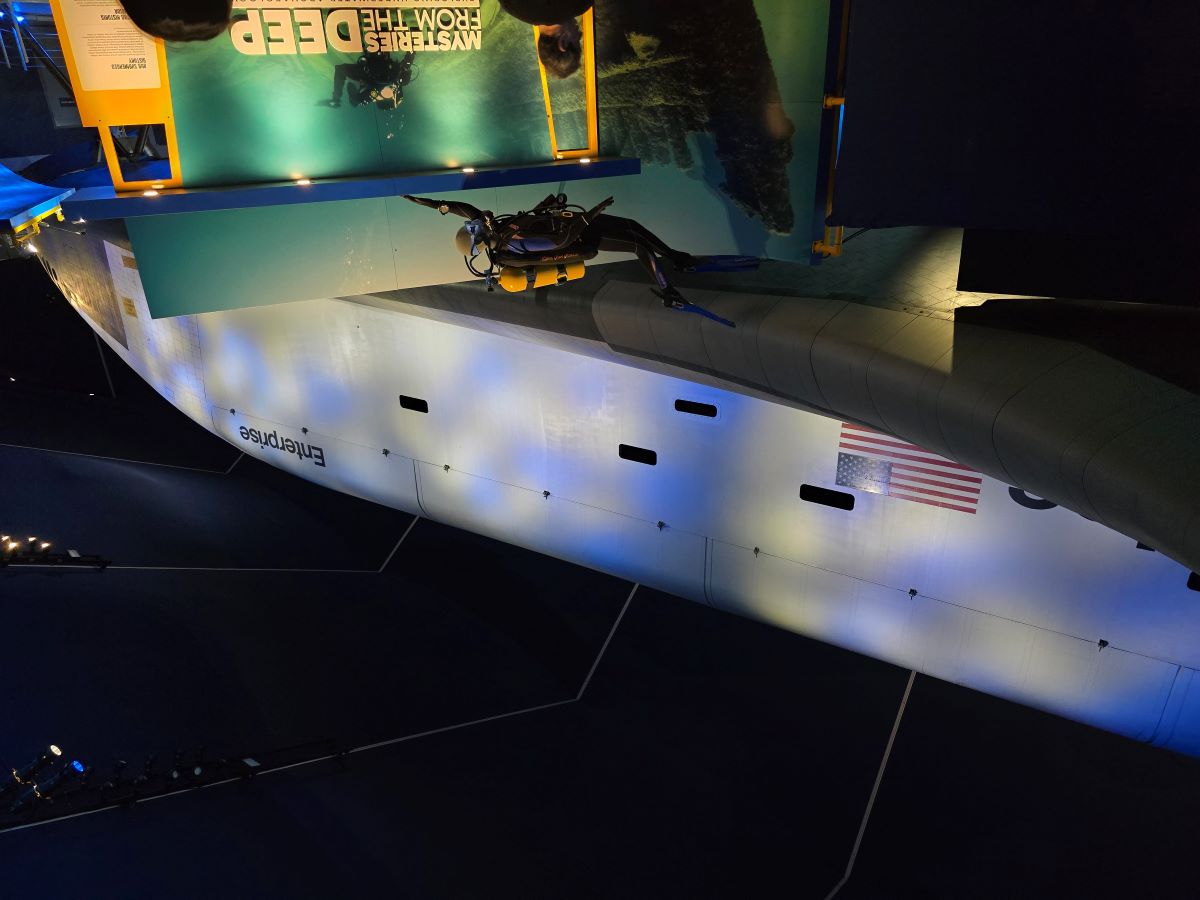

A massive Space Shuttle Pavilion was built on the western side of the flight deck, housing the Space Shuttle Enterprise (viewable only from outside), along with an underwater archaeology special exhibition.

Space Shuttle Enterprise

The Space Shuttle Enterprise was completed in 1976 as the first prototype of its kind. Originally planned to be converted for actual space flight after testing, many problems were discovered during testing (“they learned a lot”), requiring major changes to the shuttle design. So it never flew to space but made significant contributions to the entire program. It was retired in 1986. After the Columbia explosion in 2003, NASA brought it out of “retirement” for additional testing. It arrived at the museum in 2012.

I remember reading popular science works about human spaceflight as a child - most countries used disposable rockets, while the US was more advanced with reusable space shuttles, but the technology was complex and risky. Challenger and Columbia were lost in mission accidents in 1986 and 2003, respectively. After all space shuttles were retired in 2011, NASA relied on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for years to send astronauts to the International Space Station, until May 30, 2020, SpaceX rockets was used. Hey, wasn’t SpaceX’s biggest innovation precisely recoverable rockets? It seems “reusability” really is the key - things always progress through twists and turns. Elon Musk was at his peak then - electric cars, solar energy, recoverable rockets - seemingly the spokesperson for human civilization’s progress. But as they say, “Wang Mang was humble before he usurped the throne.”

Conclusion

I’m not a military enthusiast, so I didn’t really understand the dozens of aircraft on the flight deck - only the A-12 left an impression due to its unique design. I’m not very interested in grand narratives, but I do feel some connection to the daily lives and work of the officers and crew who served aboard. Let me say it again: war is cruel - may there be peace in the world.

I’ve been doing this kind of “backloaded tourism” lately - visiting without preparation, then researching the background afterwards (like Hartford, West Point). As a preview, next I’ll write about carefully planned “frontloaded tourism” with thorough preparation - the British Museum.