West Point Military Academy Half-Day Tour

(Translated from the Chinese version with the help of Claude.)

Last weekend, I took a half-day tour of the renowned West Point Military Academy. Combined with the short film and exhibitions at the visitor center, plus the tour guide’s explanations, I’ll summarize and record what I learned. Following chronological order, this can be divided into three parts: the Revolutionary War period, the academy’s glorious history after its establishment, and an introduction to modern West Point education.

Revolutionary War Period

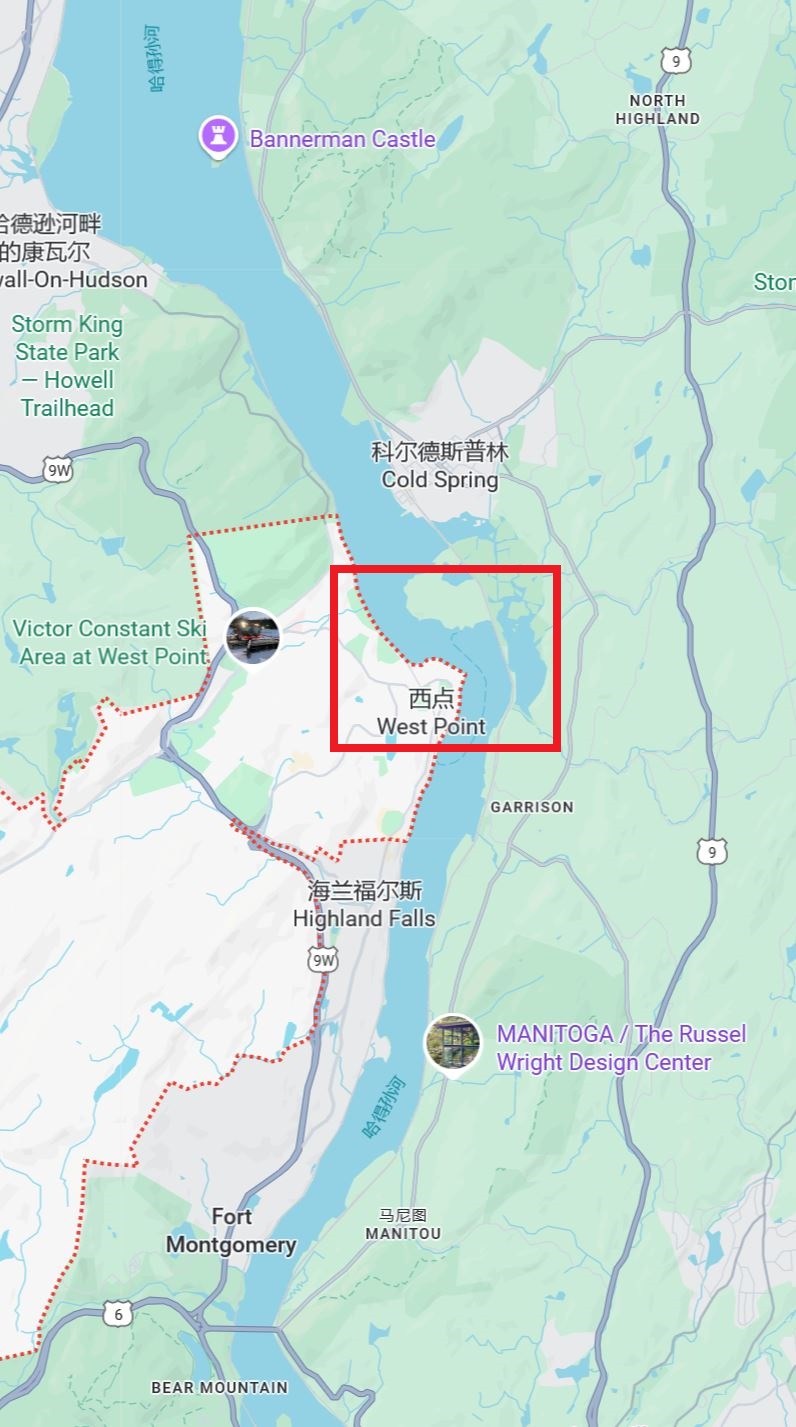

The Hudson River was an important waterway for transportation in North America, with its southern outlet at the major port of New York. If the Hudson River were controlled by the British, the independence-minded New England would be separated from other colonies. Therefore, both sides had to compete for control of the Hudson River. The Hudson River flows from north to south and narrows at West Point, with two nearly 90-degree sharp bends within 500 meters. The rapids and strong winds made navigation difficult. Building fortifications here could more effectively attack passing British ships. Washington once commented that West Point was “a key to the continent.”

Map of the West Point area

In addition to shore fortifications, the Continental Army also placed a great chain across the river to further impede British ships. The chain had to be removed each winter and reinstalled the following spring to prevent damage from ice formation. After the war, most of the great chain was melted down for other uses, leaving only 13 links, representing the original 13 colonies that declared independence.

The Continental Army had similar setups of “shore fortifications + river obstacles” at other locations along the Hudson River, such as placing chevaux-de-frise (sharpened logs) underwater between Fort Washington and Fort Lee north of Manhattan Island downstream. History proved that the water there was too wide to effectively impede British ships, but the British fleet never approached West Point, so the great chain’s effectiveness was never tested.

13 chain links

Hero, Villain, Victim

During our tour, the guide emphasized three figures from this historical period: a hero, a villain, and a victim.

The hero was Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a Polish engineer. In 1776, at only 20 years old, he came to North America and joined the Continental Army as an engineer to participate in the American Revolutionary War. In 1777, he developed successful defensive strategies for the Continental Army in the Battle of Saratoga. From 1778-1780, he directed the design and construction of most of West Point’s defensive fortifications. After the war, he returned to Poland in 1784 and led the 1794 Kosciuszko Uprising named after him (Dąbrowski, mentioned in the Polish national anthem, also participated - an unexpected connection). Like Prussia’s von Steuben and France’s Marquis de Lafayette, he became an outstanding representative of international friends who supported the American Revolutionary War.

The villain was Benedict Arnold. He achieved great success for the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. In May 1775, he participated in capturing Fort Ticonderoga, laying the foundation for the eventual victory in the Siege of Boston. In September 1777, he performed extremely courageously in the Battle of Saratoga, considered the turning point of the Revolutionary War, leading his troops to victory. After this battle, France formally allied with America, and the scales of victory began to tip toward America. In June 1778, after the British evacuated Philadelphia, he served as military commander of Philadelphia and developed good relations with Loyalists (pro-British faction). Arnold’s reasons for betrayal were complex, possibly including dissatisfaction with promotion speed, influence from his new Loyalist wife, and long-standing conflicts with Philadelphia’s civilian authorities. In 1779, Arnold began secret contact with British forces. In August 1780, Washington put him in charge of West Point’s defense, but Arnold planned to surrender the fortress to the British. In September, the plan was exposed, and he defected to New York City to join the British army.

The victim was John André. He was Arnold’s British contact who was captured by militia after meeting with Arnold. Washington proposed exchanging André for Arnold, but the British refused. Although many in the American army, including Marquis de Lafayette and Hamilton, expressed sympathy for André and even opposed the death penalty, Washington still decided to execute him for espionage by hanging. His remains were later transported back to England and buried in Westminster Abbey. Hamilton commented: “Never perhaps did any man suffer death with more justice, or deserve it less.” From legal and military perspectives, André’s execution as a spy was completely reasonable and complied with wartime law. But from a character standpoint, André was a noble, talented gentleman whose personal character was admirable.

Glorious History

- In the 1790s, Washington, Knox, Hamilton, John Adams, and others hoped to establish a military academy to train military talent, avoiding dependence on foreign allies for engineers and artillerymen during wartime, but this was opposed by Secretary of State Jefferson and others. Jefferson was very averse to European professional armies and officer classes. However, when Jefferson later became president, he recognized that a strong army was very important for defending the nascent government, plus America’s continued westward expansion increased national defense pressures. Finally, in 1802, President Jefferson authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to establish the United States Military Academy at West Point, commonly known as West Point. The early school focused on training engineers urgently needed by the U.S. military, building railroads, roads, bridges, and ports, and surveying the terrain of new western territories. All superintendents were engineering officers through 1866, when the school’s supervising organization transferred from the Corps of Engineers to the Secretary of War. The short film mentioned that the first graduating class had only two people. Now each graduating class has about a thousand people.

- 1817-1833: The 5th Superintendent, Sylvanus Thayer (Class of 1808), laid the foundation for all aspects of the school and is hailed as the “Father of West Point.”

- 1846-1848: The Mexican-American War was the first large-scale war in which West Point graduates participated.

- 1861-1865: The Civil War. West Point graduates provided 762 and 304 officers respectively for the Union and Confederate armies, up to the commanding generals of both sides. The tour guide mentioned that in 60 of the 65 major conflicts of the Civil War, West Point graduates commanded the forces.

Battle Monument, with cannons pointing downward around the area to mourn the dead and express hope for no more fraternal conflict. The nearby area is called Trophy Point, displaying many cannons captured from enemies, including from the Saratoga victory and the Civil War.

- After the war, West Point graduates continued to serve the nation in engineering construction projects, including the Washington Monument completed in 1884, and the Panama Canal completed in 1914. How about that - capable in both civil and military affairs, excelling in both fields - are you impressed? A side note: When the Washington Monument was completed, it was the world’s tallest building (169 meters), but just five years later (1889) it was greatly surpassed by the Eiffel Tower (330 meters), nearly doubling in height. The French really didn’t give any face!

- Later, West Point graduates continued to make their contributions in World War I, World War II, and other wars.

Constellation of Stars

The Long Gray Line

The exhibition at the visitor center begins by emphasizing “The Long Gray Line,” which literally refers to the long queue formed when West Point cadets march in formation wearing gray uniforms, symbolizing the spiritual inheritance among West Point alumni. The five outstanding graduate representatives above are absolutely an all-star lineup, from left to right:

- Ulysses S. Grant, Class of 1843, Union Army commanding general in the Civil War, later served as U.S. President. Posthumously promoted to General of the Armies (six-star general) in 2024.

- John J. Pershing, Class of 1886, American Expeditionary Forces commander in World War I, the first General of the Armies in U.S. military history, and the only person to receive this rank while living.

- Douglas MacArthur, Class of 1903, served as Superintendent 1919-1922, Allied Southwest Pacific Theater commander in World War II, five-star general.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, Class of 1915, Allied European Theater commander in World War II, five-star general. Later served as U.S. President.

- Omar Bradley, Class of 1915 (Eisenhower’s classmate), important Allied commander in North Africa and Europe during World War II, five-star general.

The Class of 1915 is called “The Class the Stars Fell On,” with 59 out of 164 graduates (36%) achieving general rank. Before this, this title belonged to the Class of 1886 (Pershing’s class), with 25 out of 77 graduates (32%) becoming generals. Both groups happened to coincide with two world wars - circumstances create heroes.

The tour guide also mentioned that the three 20th-century five-star generals had different personalities: MacArthur placed great emphasis on military discipline and tradition, excelled academically, and graduated first in his class; Eisenhower had average grades but demonstrated strong interpersonal skills and a pragmatic attitude; Bradley was between MacArthur and Eisenhower.

Two other generals, though not among the “starting five,” are also worth mentioning:

- Henry “Hap” Arnold, Class of 1907, U.S. Army Air Forces commander in World War II, awarded the rank of General of the Army (five-star general) in 1944. In 1947, the Army Air Forces became independent as the Air Force. In 1949, he was “laterally transferred” to become a five-star Air Force general, and remains the only five-star Air Force general to date. He thus became the only officer to hold five-star rank in two branches of the U.S. military.

- Robert E. Lee, Class of 1829, served as Superintendent 1852-1855, Confederate Army commanding general in the Civil War. Unfortunately, he chose the wrong side, otherwise his historical status would be completely different.

Military Ranks 101

Seeing so many five-star and six-star generals made me a bit dizzy, so I looked it up. One star: Brigadier General, two stars: Major General, three stars: Lieutenant General, four stars: General. Five-star rank is generally reserved for wartime use, with nine people receiving it total: one Air Force General of the Air Force (Henry Arnold), four Navy Fleet Admirals, and five Army Generals of the Army, four of whom graduated from West Point (the other was George Marshall, after whom the post-war Marshall Plan for European aid was named).

Going higher, the rank is colloquially called six-star general or super general. The Navy version is called Admiral of the Navy. Congress created this rank in 1899, intending to award it to George Dewey who commanded the Battle of Manila Bay in the 1898 Spanish-American War. However, when the president made the nomination, it was written incorrectly as “Admiral in the Navy” rather than the new rank Congress had just created. In 1903, the president re-nominated to correct the error. The congressional act also stipulated that when Dewey died, the rank would cease to exist - truly unprecedented and unrepeatable.

The Army version is called General of the Armies of the United States, which sounds impressive enough. When awarding it to Pershing, the president (different one) again made an error, using “general in the Army.” On the one hand, this makes it seem like amateur hour, but on the other hand, these title distinctions are really too subtle - making mistakes is quite understandable.

In 1976, America’s bicentennial, Washington was posthumously awarded six-star general rank. The stated reason was that his rank at the time was Lieutenant General, but how could the Founding Father’s rank be surpassed by later generations? Congressman Lucien N. Nedzi’s opposition makes a lot of sense to me: Washington’s status is already so high that giving him a modern army rank would only make Congress look ridiculous. “It’s like having the Pope offer to make Christ a cardinal.”

In 2021, other congressmen stirred things up, saying the 1976 law authorizing Washington’s promotion actually lowered Grant’s rank appointed in 1866. So in 2024, Grant was also posthumously awarded six-star general rank. Can’t congressmen do more practical work for the people and less of this meaningless nonsense?

Modern West Point

The current West Point introduction felt like their major recruitment promotion exhibition - cadets get four years of tuition, room and board, textbooks, medical insurance, and dental insurance all covered, plus a small monthly stipend. Those who understand know how substantial this package is. But graduates must serve in the Army for at least five years after graduation.

Educational Philosophy

This Greek temple-style structure embodies West Point’s educational philosophy. The three core values at the base - Duty, Honor, Country - are West Point’s motto. The four pillars represent Academic, Military, Physical, and Character, symbolizing comprehensive cadet development. “Leaders of Character” at the top symbolizes West Point’s goal of cultivating leaders of high character.

In line with physical development, the school places great emphasis on various college sports activities. MacArthur emphasized: “Every cadet an athlete.”

Coat of Arms

The coat of arms features a sword (symbolizing war), Athena’s helmet (symbolizing war and wisdom), a bald eagle (symbolizing America), 13 arrows (symbolizing the original 13 colonies that declared independence), and olive branches (symbolizing peace). It also includes the school motto and founding date.

The exhibition also briefly introduced the four-year educational content, which I won’t elaborate on here. Interestingly, the four grades of students at West Point aren’t called freshman/sophomore/junior/senior, but plebes/yearlings/cows/firsties.

Campus Tour

The museum next to the visitor center (free admission) has been closed for a month due to air conditioning problems, and it’s unclear when it will reopen, so we had to skip it this time. Due to West Point’s sensitive nature, outsiders aren’t allowed to freely tour the campus but must take designated buses with a guide. We went on Sunday morning, and the bus tour skipped the cadet chapel because of worship services. We took some interesting photos on campus - some were snapshots from the bus, others taken from far away, so please bear with the quality.

Women's soccer team practicing in the indoor football facility

Football stadium

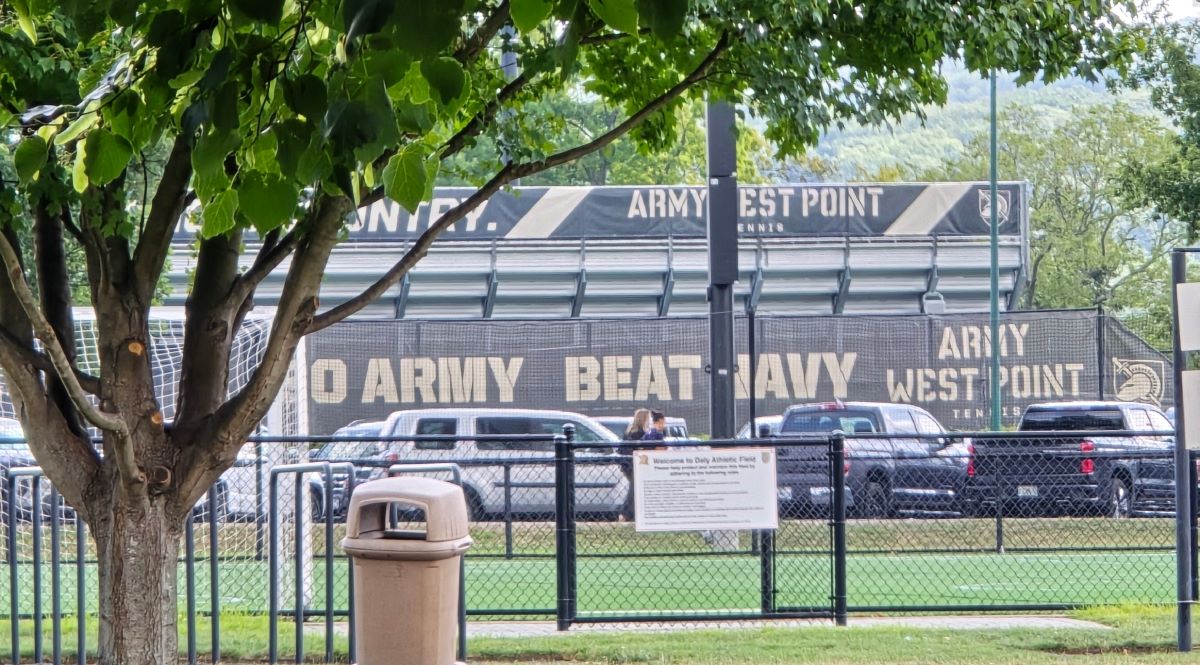

'Army Beat Navy' slogan on the training field. There's even a hotel near West Point called Beat Navy House.

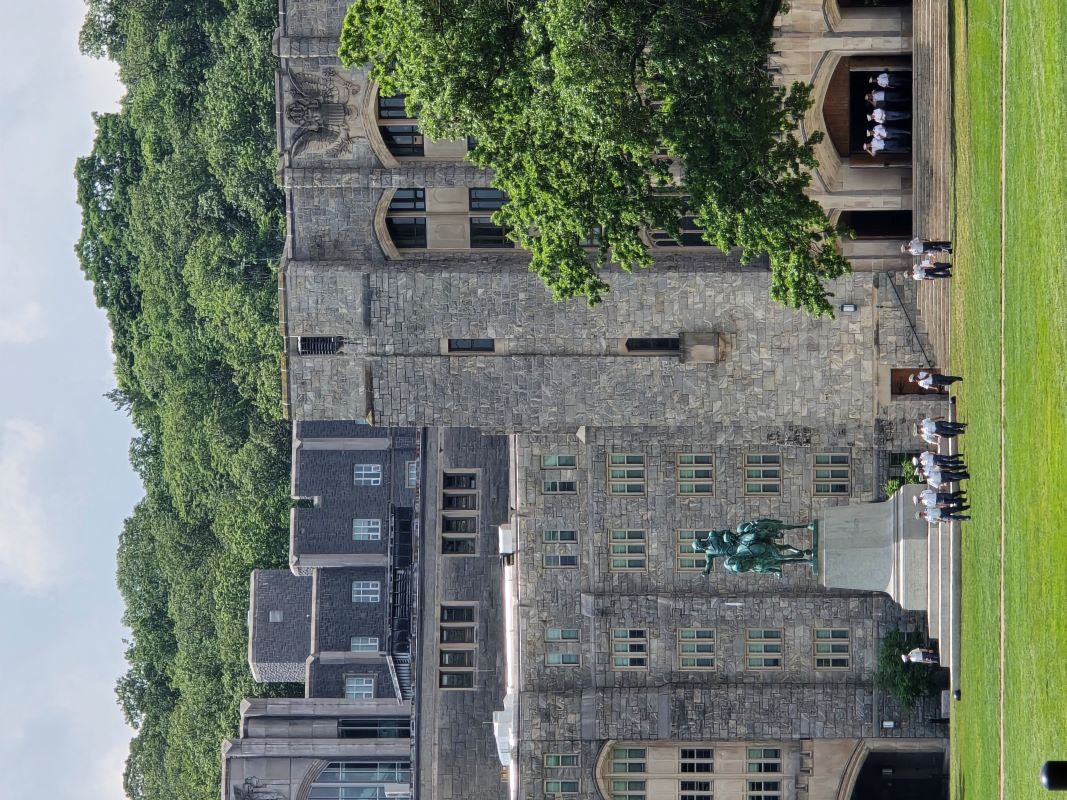

In the hot midday sun, under the watchful gaze of their alumnus Grant's statue, cadets train on the parade ground.

Cadets in uniform walking out of the main academic building, next to Washington's statue.

Taylor Hall, where the Superintendent's office is located. The tower is 55 meters high and is the world's tallest all-stone masonry building.

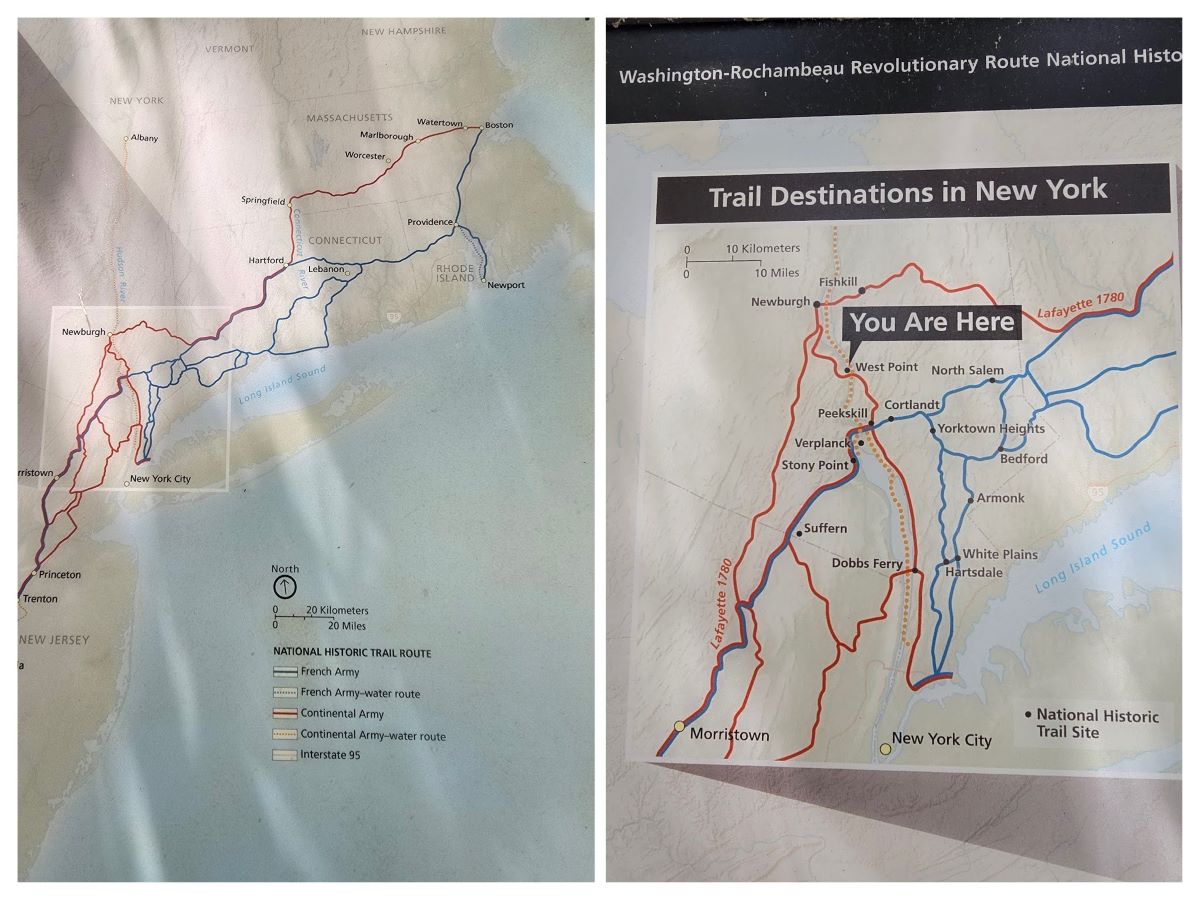

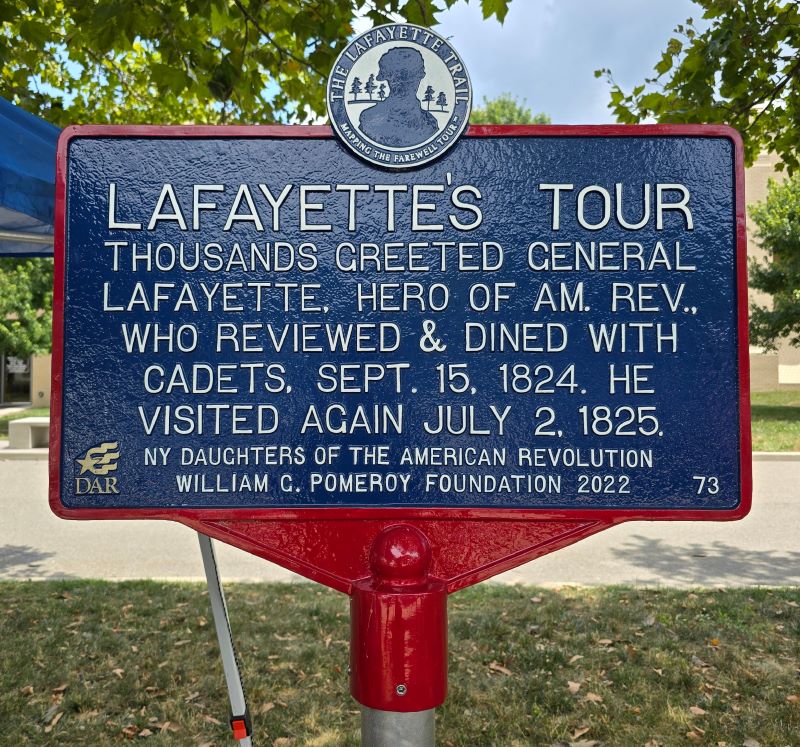

Before leaving, I discovered that outside the visitor center there were also signs for the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route and the distinctive red-framed, blue-background, white-lettered sign commemorating Marquis de Lafayette’s 1824-1825 visit to America - an unexpected connection with Hartford that caught me off guard.

Revolutionary Route passes through West Point

Marquis de Lafayette visited West Point on September 15, 1824, meeting with cadets and dining with them. He came again on July 2, 1825, on his return journey.

Last I’ll leave you with the video for the West Point stop from The Lafayette Trail: